Bringing your medical device to the market is an exciting yet challenging journey. The first milestone of this journey is to determine where your medical device stands in terms of the FDA classification.

Understanding your healthcare device classification is not just a regulatory formality. It’s what defines your FDA submission strategy, the pathway to potential FDA clearance, the risk management approach, and the level of development and testing rigor.

What is a medical device according to the FDA?

According to Section 201(h) of the FD&C Act, a medical device is any instrument, machine, implant, or in vitro reagent intended for medical use or making medical claims. By medical use, the FDA understands the purpose of diagnosing, treating, or preventing diseases.

Examples of products considered medical devices

The FDA regulates all medical devices marketed in the U.S., so anything from thermometers to advanced robotic surgery systems can fall under the term ‘medical device’. Here are some examples of products subject to device registration:

- Simple medical devices: thermometers, bandages, gloves, and other everyday healthcare items.

- Complex medical devices: medical imaging devices, infusion pumps, implantable devices, and other tools that involve technology and carry a higher risk.

- Software as a medical device (SaMD): mobile apps for medical image analysis, medication dosage algorithms, and other software that performs medical functions without being a part of a physical hardware device.

Examples of what is not a medical device

Not all healthcare or wellness products fall under the umbrella of the FDA classification, as certain software functions are legally excluded from the FDA’s definition of a ‘medical device’.

These products include applications and tools designed for:

- Maintaining a healthy lifestyle (fitness trackers, meditation apps, sleep monitoring applications meant for general wellness, etc.).

- Managing the operational or administrative aspects of the healthcare facility (hospital inventory solutions, practice management systems, etc.).

- Digitizing the existing patient records, as long as they don’t suggest any clinical interventions.

- Serving as conduits for medical data with no interpretation (PACS for basic image management, LIS for raw data handling, etc.)

Why you need to classify your medical device early on

Medical device manufacturers shouldn’t wait until the last minute to identify where their devices stand on the spectrum of the FDA classification system. They should take care of it long before the development starts, as the classification dictates the entire direction of the product development lifecycle:

- Development strategy — Knowing your class early on allows you to identify the necessary level of development rigor, including design controls, testing activities, and documentation artifacts to minimize the risk of costly rework.

- Regulatory pathway — Each medical device class follows a distinct regulatory pathway to market, with high-risk devices requiring the strictest approval process, while low-risk devices are exempt from extra reviews.

- Resource allocation — The time and budget spent on designing, developing, testing, and submitting a high-risk device are drastically different from those of a low-risk medical device.

- Risk management framework — Knowing your device class right at the beginning allows you to shape a risk management framework that meets the regulatory requirements, plus improves the safety and quality of your product in line with customer expectations.

- Investor and stakeholder communication — The de-risked development process makes your project more attractive to investors, grant agencies, and potential healthcare partners.

Overall, identifying where your healthcare product sits allows you to dodge the costly and unpleasant surprises related to misclassification or gaps in documentation.

Types of the FDA’s premarket submissions

The FDA outlines five main premarket submission pathways, with each pathway tailored to the risk level and novelty of the device.

Premarket Notification 510(k)

This type of premarket submission applies to exempt Class I devices and the majority of Class II devices and is intended to demonstrate that the quality and safety of a new device is comparable to a legally marketed predicate device.

Premarket Approval (PMA)

High-risk Class III devices undergo the most stringent submission pathway, requiring a detailed report of all clinical investigations to ensure the device has been clinically validated.

Investigational Device Exemption (IDE)

If medical device manufacturers want to use an unapproved medical device to collect cliniсal data on the safety and effectiveness of the device, they need to apply for and receive an Investigational Device Exemption from the FDA. This is usually the case with high-risk investigational devices.

De Novo classification request

When a medical device manufacturer develops a low-to-moderate risk device with no similar marketed counterpart, they must submit a De Novo classification request for direct FDA review and classification.

Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE)

If the high-risk medical device is intended for the treatment or diagnosis of rare diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 8,000 U.S. individuals per year, the HDE submission offers a more streamlined route to the market compared to the PMA submission.

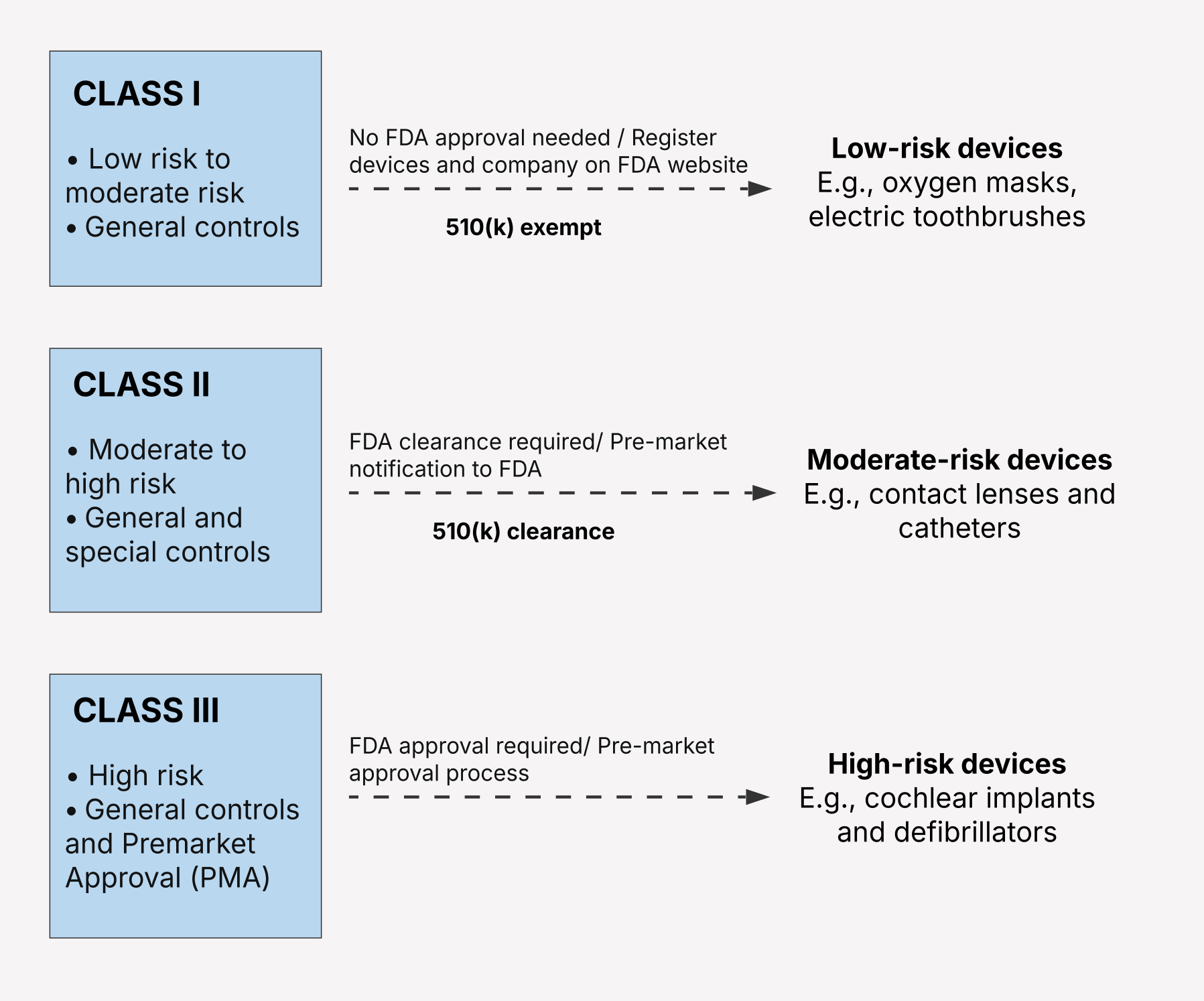

Overview of the FDA medical device classification system

The FDA’s medical device regulatory classification follows a risk-based approach to classify devices, including the intended use of the device and its potential risk to the patient/user in case of the device’s malfunction. The FDA categorizes medical devices according to a three-tiered classification system (Class I, Class II, Class III), where each class is associated with a different level of regulatory control.

Each device category is subject to specific regulatory controls — including general, special, or premarket approval — to provide reasonable assurance of the safety and effectiveness of the device.

Regardless of their class, most devices are subject to General Controls, including Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP), labeling, registration, and listing requirements, and other stipulations. Higher-risk device classes also have additional, more stringent requirements, in addition to the General Controls.

Class I medical devices

A medical device fits into the Class I category when it’s low-risk and poses minimal potential for harm to the patient or the user should it fail or be used incorrectly. Class I devices are relatively simple and aren’t designed to support life or prevent health conditions.

According to the FDA, 47% of medical devices belong to this category. Common examples of Class I devices include elastic bandages, electric toothbrushes, and manual stethoscopes.

The regulatory pathway for Class I medical devices

The FDA states that 95% of Class I devices are outside the scope of the regulatory process, meaning that they’re partially or entirely exempt from FDA premarket regulatory requirements, particularly the Premarket notification process (Premarket notification 510 (k)).

However, Class I devices still need to go through the General Controls of the FD&C Act:

- Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP)/ Quality System Regulation (QSR) — Class I devices must be manufactured according to a quality management system appropriate to a given device to ensure the device’s safety.

- Labeling requirements — Labels for Class I devices must be accurate and non-misleading and include adequate directions for use.

- Establishment registration and device listing — Device manufacturers must register their facilities with the FDA and list their devices.

- Medical Device Reporting (MDR) — Reporting serious adverse events is mandated by the FDA if a device may have caused or contributed to someone’s death, injury, or malfunction.

Non-exempt Class I devices

Regardless of the low associated risk, some Class I devices may still require a premarket notification (510(k)) or Special Controls because of the nuances in their nature or intended use.

Due to the sheer volume of medical devices, it’s hard to narrow down an exact list. Some examples of such devices include:

- Innovative devices, devices with novel designs, or those based on new technologies, for which the FDA has no well-established precedent.

- Devices that meet the ‘reserved’ criteria, i.e., those of substantial importance or with unreasonable risk.

- Devices intended for high-risk populations, etc.

So, even if your device appears to be low-risk, don’t assume it’s exempt from the Special Controls. Make sure to check the specific classification regulation for your device type in 21 CFR Parts 862-892 and the FDA's databases.

Class II medical devices

The Class II medical device category includes medical devices that pose a moderate to potentially high risk to the patient. The risk associated with Class II medical devices can stem from their complex functionality, greater invasiveness, or a significant risk of harm in the case of malfunction. Infusion pumps, radiology imaging processing software, clinical decision support software, and ECG data analysis apps are common examples of Class II devices.

The regulatory pathway for Class II medical devices

Because Class II entails a potentially higher risk, just General Controls are not enough to prove their safety. That’s why Class II devices must also meet Special Controls, which are device-specific requirements that include:

- Performance standards — Specific radiation-emitting electronic products must meet measurement requirements to be deemed safe and effective.

- Postmarket surveillance — After the device has been released to market, the manufacturer must gather real-world performance data on its safety and effectiveness.

- Patient registries — To monitor the long-term impact of the device, manufacturers must collect and track data about device users.

- Special labeling requirements — Along with standard labeling, Class II medical devices must have specific warnings and instructions for use.

- Premarket data requirements — In their Premarket Notification, device manufacturers are mandated to include specific types and amounts of data to show that their device is substantially equivalent to a marketed predecessor device.

- Guidance documents — Although manufacturers aren’t legally required to adhere to the FDA’s roadmaps for device design, best testing practices, and other recommendations, they’re highly encouraged to do so for a faster and smoother submission process.

- Device tracking — Certain devices must be thoroughly tracked through the distribution chain, and, in some cases, down to the patient level.

The 510(k) Premarket Notification Process

Most Class II devices enter the market through the Premarket Notification 510(k) submission process. The submission typically contains information about the device's design, manufacturing, labeling, performance testing, and comparison to the predicate device.

At the core of the Premarket Notification 510(k) process is the substantial equivalence concept that evaluates the safety and effectiveness of a new device compared to that of a device that’s already legally on the market. Substantial equivalence doesn’t require an exact match. It’s enough for a new medical device product to demonstrate a similar level of safety and effectiveness as the predecessor device.

If the FDA finds the device substantially equivalent, it issues a clearance letter, allowing the manufacturer to market the device.

De Novo classification request

If there’s no predicate device to claim substantial equivalence of a product, manufacturers are allowed to submit a De Novo request. Without this request, novel devices risk being classified in the Class III category, thereby requiring a more rigorous Premarket Approval process.

Additionally, if a manufacturer is uncertain whether their novel device falls under Class I or Class II, they can utilize a De Novo submission pathway to allow the FDA to evaluate the risks associated with their device and classify it accordingly.

Class III medical devices

Recognized for the highest profile among all device types, Class III medical devices are devices intended to support or sustain human life or play a critical role in preventing harm to human health. If the device malfunctions, it can potentially pose a significant risk of illness or injury to the user.

Class III devices are typically highly invasive and rely on complex technologies that enable critical functionalities. Examples of Class III devices include implantable pacemakers, AI-based diagnostic tools that recommend the optimal course of action, and remote monitoring software integrated with high-risk devices.

The regulatory pathway for Class III medical devices

According to the FDA classification regulations, all Class III devices require Premarket Approval (PMA) before they can enter the US market unless they are pre-amendment devices or have been found substantially equivalent to the devices for which a PMA has been unnecessary. The PMA submission is the most stringent regulatory pathway that mandates manufacturers to submit extensive clinical data to support claims made for the device.

Besides clinical data, the PMA process involves a comprehensive regulatory review:

- Detailed device description — Class III device manufacturers are required to provide exhaustive information about the device, including its components, operating principles, and more.

- Results of non-clinical testing — Along with clinical data, manufacturers must include non-clinical data obtained from bench testing and animal studies to prove that the device is reasonably safe to be tested in humans.

- Manufacturing information — The PMA submission also demands a step-by-step breakdown of how a medical device was made and which quality controls are in place.

- Proposed labeling — This section dwells on the labeling information for users and/or healthcare professionals.

- Summary of safety and effectiveness data — A snapshot of all the data provided with the PMA application gives the FDA a comprehensive image of the overall evidence.

Keep in mind that the PMA submission doesn’t relieve manufacturers of ongoing responsibilities. Class III devices still must adhere to Good Manufacturing Practices, MDR, device tracking, risk management activities, and, potentially, post-approval studies.

Post-market surveillance

The FDA has the authority to order Class II and Class III device manufacturers to run surveillance studies after the device has been brought to market. Post-market surveillance is initiated if the device meets certain criteria:

- Its failure can lead to serious adverse health consequences.

- The device is intended to be implanted in the human body for more than 1 year.

- The device is life-sustaining or life-supporting and is designed for non-clinical use.

- The device will be widely used in pediatric care.

How to determine the class of your medical device

Here’s a step-by-step framework to determine the correct classification for your medical device:

1. Identify the intended use and indications for use of the device — Pin down the general purpose of the device and specify the disease, condition, or target patient population for which the device is intended to be used.

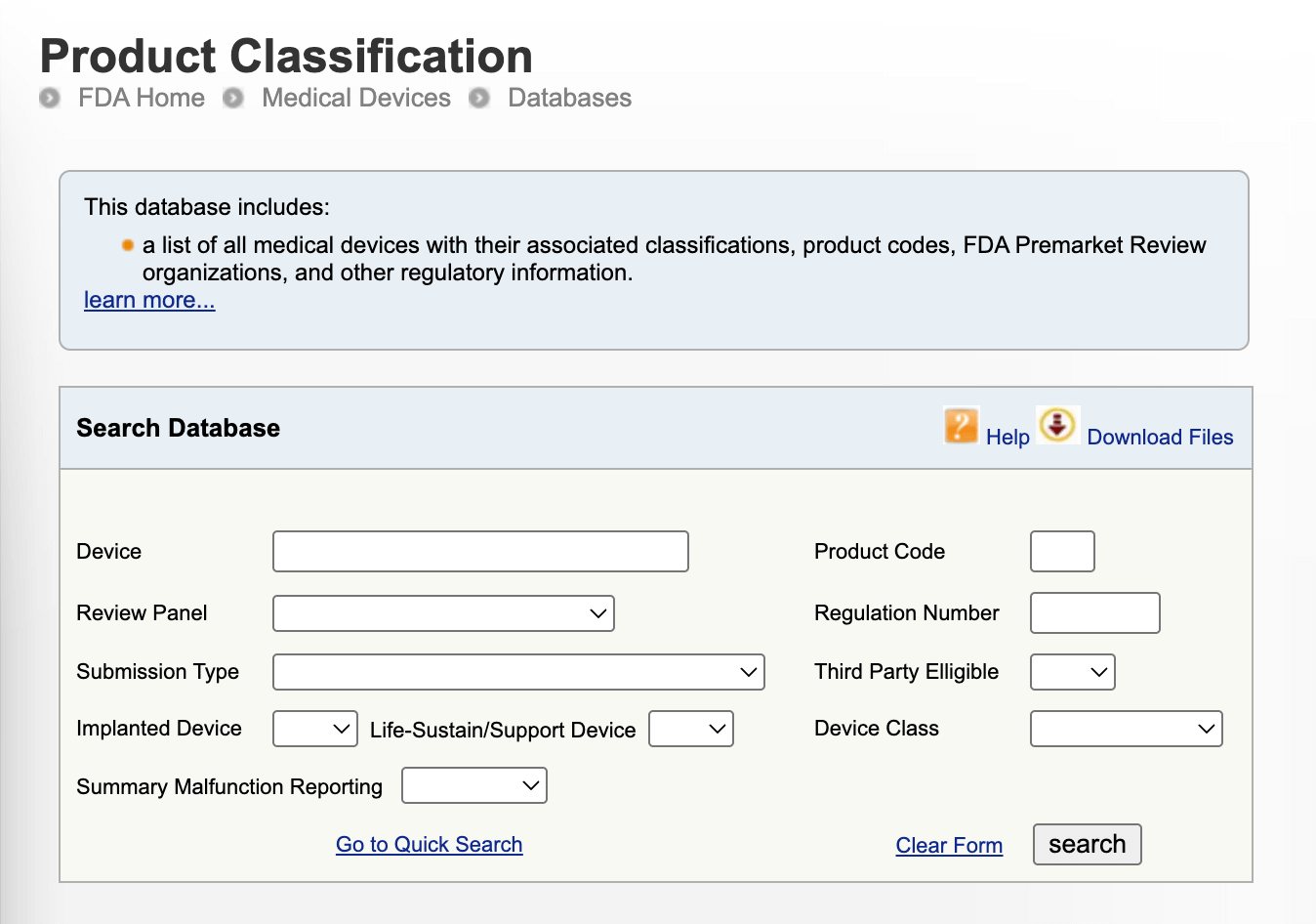

2. Find the appropriate FDA product code and regulation number in the FDA Product Classification Database — As a starting point, go to the FDA’s searchable database to find the matching description of the device to get a better understanding of the applicable regulatory pathway, premarket submission type, and the overall safety expectations.

3. Look for predicate devices if applicable — If your device is likely to qualify for the 510(k) pathway, you can locate a suitable predicate device in the FDA's 510(k) Premarket Notification Database to determine substantial equivalence.

4. Understand the risk profile of your device — Even if you’ve identified the predicate device to build upon your substantial equivalence argument, you still need to run an independent risk assessment to outline the Special Controls your device needs, shape your testing strategy, and tailor other essential elements of your regulatory submission and post-market activities.

5. Review classification panels (by medical specialty) — The FDA lists over 1,700 generic types of devices that span 16 medical specialties, giving device manufacturers additional context into the specific clinical and scientific concerns the FDA will focus on when reviewing the device.

6. Seek FDA feedback if uncertain — If you’re struggling to classify your novel device, face conflicting classifications for similar devices, or want early FDA feedback, you can formally ask the FDA for their opinion by submitting a 513(g) request.

Challenges in software as a medical device classification

As a healthcare development company with extensive experience in bringing digital products to market, we’re well aware of how challenging and confusing SaMD classification can be. Unlike traditional hardware-based devices, SaMD is known for its intangible nature, continuous evolution, and reliance on data-driven algorithms, so its regulatory status sometimes might fall into regulatory uncertainty.

According to the FDA, software as a medical device is standalone software used for diagnostics, disease monitoring, or therapeutic decision support. Despite its unique nature, SaMD is classified into three groups (Class I, Class II, Class III), just like other medical devices.

Here’s what to take into account when classifying your SaMD:

- Intended use and claims — Just like with other devices, the FDA’s approach to SaMD depends on what the product is designed for. The greater the impact the software has on clinical decision-making, the higher its class will be.

- Autonomy — The more influence the software has on clinical decisions, the higher class it’ll end up in. SaMD that informs decisions is typically qualified as lower-risk compared to those that recommend actual interventions.

- Explainability — If the SaMD leverages AI/ML-based functionality built on black-box models, it’s likely to be subject to more stringent reviews.

- Update mechanisms — When powered with adaptive learning or real-time updates, SaMD typically falls under Special Controls and/or postmarket surveillance.

- Predicate device availability — Many novel SaMD products follow a De Novo submission pathway to demonstrate substantial equivalence.

- Regulatory exemptions — Not all SaMD qualify as medium or high risks. Software used for general wellness, lifestyle tracking, or administrative support may fall outside the scope of FDA regulation or be classified as low-risk Class I devices.

Develop healthcare software that’s audit-ready from day one

When developing a healthcare device for the U.S. market, FDA compliance is one of the first and most crucial aspects to address early. The regulatory status of your medical device sets the tone for everything that follows, including your software development lifecycle, quality management system, documentation, and launch.

At Orangesoft, we help medtech innovators introduce FDA-compliant products to the market faster by taking care of all things software. From secure coding practices to quality system documentation to the selection of explainable AI/ML models, our software development company helps you ensure compliance from inception, to save time and avoid roadblocks down the line. Feel free to reach out to our team of experts.